Games for the Ambitious

The engineer Charles Darrow lost his job in the stock market crash of 1929. After spending some time unsuccessfully looking for work, he created a board game based on ambition and property speculation, which were popular issues at the time. He originally intended it to be marketed by Milton Bradley, popularly known as MB, or by Parker Brothers, two of the most important board games brands of the era. The directors at Parker turned down the game, considering it to be long, boring and with unclear rules and objectives. Luckily, Charles Darrow refused to give up and brought out 500 copies of the game himself, which he sold at Wanamaker’s department store in Philadephia under the title Monopoly. They soon sold out and the managers at Parker changed their minds and decided to market it themselves. Since then, Monopoly has become one of the biggest selling board games in history and a pioneer in terms of board games as cultural consumer products. And it was also the first of many games designed for the ambitious, in this case in the context of the most savage form of capitalism.

Like a Russian doll, the history of Monopoly is marked by layers of ambition and a lack of scruples. It is itself an evolution (you could say a copy) of The Landlord’s Game, a board game created by Elizabeth Magie in 1904 with the educational purpose of showing people how capitalism impoverished the general population while enriching landowners. In Risk (Albert Lamorisse, 1957, Hasbro), another 20th century classic, ambition takes the form of a nervous itch that presents itself when you realise that you are close to victory and that to attain it you need to wipe out your weakest rivals. At the end of the last

At the end of the last century there was another board game revolution, spearheaded by Catan (Klaus Teuber, 1995, Devir). In this case, you are the colonisers of an island and must be the first ones to win ten points by founding towns and building roads. To do that you need to dispose of certain materials that can only be accessed by those who can acquire them or by those who are ambitious and barter them with other players or sell them at prices that are worthy of being described as usury. The issue of ambition is also present in 7 Wonders (Antoine Bauza, 2010, Asmodee), another recent prize-winning game. In it you have to build a wonder by combining the arts, the sciences and industry while, of course, imposing oneself militarily on one’s adversaries.

At the end of the last century there was another board game revolution, spearheaded by Catan (Klaus Teuber, 1995, Devir). In this case, you are the colonisers of an island and must be the first ones to win ten points by founding towns and building roads. To do that you need to dispose of certain materials that can only be accessed by those who can acquire them or by those who are ambitious and barter them with other players or sell them at prices that are worthy of being described as usury. The issue of ambition is also present in 7 Wonders (Antoine Bauza, 2010, Asmodee), another recent prize-winning game. In it you have to build a wonder by combining the arts, the sciences and industry while, of course, imposing oneself militarily on one’s adversaries.

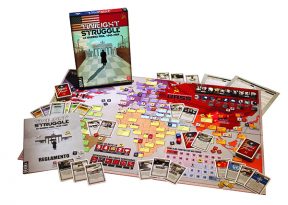

One of the most fertile fields for the ambitious is politics and there are many games that deal with it. For example, in Campaign Manager 2008 (Christian Leonhard and Jason Matthews, 2009, Gen-x Games) we can choose whether to direct the campaign of Obama or McCain, while in Cold War (Sébastien Gigaudaut and David Rakoto, 2007, Edge Entertainment) and Twilight Struggle (Ananda Gupta Jason and Matthews, 2010, Devir) we must control the Europe of the cold war period. In the game 1714: el cas dels catalans (Ivan Prat, 2014, Devir), political ambition drives us to support one of the powers carving up 18th century Europe. A different case is that of Coup (Rikki Tahta, 2013, Zacatrus), since the gameplay is based on dialogues and political intrigue takes on a new dimension since the players have to betray themselves in order to achieve their goals.

One of the most fertile fields for the ambitious is politics and there are many games that deal with it. For example, in Campaign Manager 2008 (Christian Leonhard and Jason Matthews, 2009, Gen-x Games) we can choose whether to direct the campaign of Obama or McCain, while in Cold War (Sébastien Gigaudaut and David Rakoto, 2007, Edge Entertainment) and Twilight Struggle (Ananda Gupta Jason and Matthews, 2010, Devir) we must control the Europe of the cold war period. In the game 1714: el cas dels catalans (Ivan Prat, 2014, Devir), political ambition drives us to support one of the powers carving up 18th century Europe. A different case is that of Coup (Rikki Tahta, 2013, Zacatrus), since the gameplay is based on dialogues and political intrigue takes on a new dimension since the players have to betray themselves in order to achieve their goals.

In recent years, board games have allowed the fans of series to live the experiences of their heroes. One of the most obvious cases of that is A Game of Thrones: The Board Game (Christian T. Petersen, 2011, Edge Entertainment), in which one must take control of the houses of Westeros in order to obtain the prized iron throne. Luckily, not all great successes are grounded in ambition. Moreover, the good news for the unambitious is that we are now living the third revolution in board games, encapsulated by a powerful storyline that goes beyond a game and cooperation between players.

In recent years, board games have allowed the fans of series to live the experiences of their heroes. One of the most obvious cases of that is A Game of Thrones: The Board Game (Christian T. Petersen, 2011, Edge Entertainment), in which one must take control of the houses of Westeros in order to obtain the prized iron throne. Luckily, not all great successes are grounded in ambition. Moreover, the good news for the unambitious is that we are now living the third revolution in board games, encapsulated by a powerful storyline that goes beyond a game and cooperation between players.

This article was published in RAR, a newspaper supplement of the Diari Ara